Is Lithium the “White Gold” Dust of the Future?

- Manesha Sundar

- Nov 27, 2023

- 3 min read

Home to the world’s largest lithium reserves, Chile is at the centre of one of the world’s highest-growth industries. Lithium is integral in the energy transition to make batteries for electric vehicles (EV), with the South American country holding over 9 million tonnes of the metal in reserves (approximately 30% of world supply), closely followed by vast reserves held in Australia. Traditional lithium supply is expected to increase by over 300% between 2021 and 2030, in conjunction with direct lithium extraction (DLE) and direct lithium to product (DLP), acting as promising drivers for the industry to respond to demand.

With countries looking to protect their natural resources, the industry faces a tough balancing act between surging demand for raw materials and constrained supply. Indeed,

in April this year, Chile’s President Gabriel Boric announced the nationalisation of its lithium reserves, indicating that future lithium contracts would only be issued as public-private partnerships controlled by the state. Moreover, like other commodity markets, price volatility appears to be an issue in the lithium market due to a lack of price transparency. Bilateral negotiations are the primary method of sales in the lithium market, whereby long-term agreements between producers and battery makers (or sometimes even car makers) are made using fixed prices set by producers.

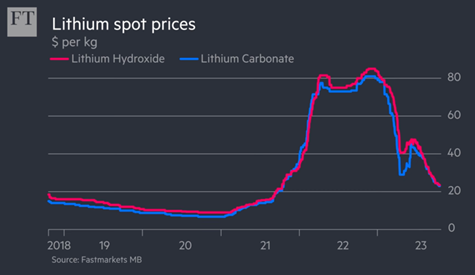

This contrasts with more mature markets such as copper or aluminium where the industry has the aid of a reference point, adopting index pricing. Put in context, Lithium Hydroxide at the beginning of 2023 was ~$85/kg which compares to the current trading price close to $28/kg, revealing a drop in price by two-thirds in less than a year. Robin Martin, Head of Market Development at the London Metal Exchange (LME), argues that shifting to index-based pricing is a solution to combat these price fluctuations and can provide greater flexibility and security with supply for battery and car makers. While almost no lithium trading takes place now on the open market like the LME, which dates to 1571, the Exchange’s efforts to enforce environmental and social standards in the metals market might be a call for change. LMEpassports were launched in October 2021, as a way for LME-listed brands to electronically register their ESG credentials, which is of increasing importance for investment managers likewise.

However, evidence highlights a notable fall in demand growth for the EV industry, mainly driven by a recent struggle to persuade buyers to make the transition from petrol or diesel. With electric vehicle sales estimated (in March) to be 67% of new car sales in 2027, The Office for Budget Responsibility cut its forecast by half to 38%, mainly justified by falling fuel prices and higher interest rates. Reluctance to switch from consumers also emerges from many factors such as EVs being more expensive than petrol cars, concerns over charging infrastructure as well as poor publicity about charging and safety. As the zeal from the early adoption phase has waned now, the mass market and sceptics are the targets to convince moving ahead. The UK’s decision in September to delay the ban on new petrol car sales from 2030 to 2035 will perhaps further postpone the swift energy transition as planned.

All in all, one thing is for certain – demand for lithium and other critical minerals for green energy is only set to surge in the future. With sustainable production at the forefront of agendas, this may mean more government intervention to ensure sustainable production while minimising a strictly top-down approach in mining and extraction practices to protect ecosystems and indigenous communities. The ongoing energy transition is certainly a global revolution for businesses and responses in the metals market will be one to look out for.

Comments